Re-enchanting the World with G.K. Chesterton: Re-enchantment as a Spiritual Discipline

by Rebekah Valerius

“Religion is returning from her exile; it is more likely that the future will be crazily and corruptly superstitious than that it will be merely rationalist.”

~ G.K. Chesterton[1]

There is much talk today among Christians that we live in a disenchanted age. The need for re-enchantment — the need to see the world not as an impersonal and meaningless collection of matter and energy, but as a purposeful creation of a personal God — is hardly disputed. Though a case can be made, I think, that disenchantment has exhausted itself and enchantment is returning from its exile, enough disillusionment remains that we must attend to it in some kind of systematic way.[1] Similarly, as enchantment returns, we must be able to distinguish between its good and bad forms (as history reveals that it can be instantiated in destructive ways). Evidence suggests that enchantment is returning with a raging ferocity, not unlike a starved bear that has just emerged from a long hibernation. Years of deprivation have resulted in meaning being read into anything and everything in ways that might not be true or edifying.[2]

Thinking of this re-enchantment as a spiritual discipline not only helps systematize the process to some degree, but it can guard against less desirable approaches to understanding the world as being charged with meaning.

G.K. Chesterton embodies this spiritual discipline in a way like no other. He saw disenchantment and was affected by it deeply during his time in art school. Unlike others of his age, he could not compartmentalize the meaninglessness. Instead, he examined the disenchanted assumptions down to their deepest roots, a process he lays out in his book Orthodoxy. He claims that it was atheists and skeptics themselves who brought him back to Christianity, writing, “They sowed in my mind my first wild doubts of doubt.”[3] By challenging the assumption that the world is meaningless, his work systematically re-enchanted (for many, including me) not only the world but also the Christian faith.

Granted, in almost any book on spiritual disciplines, you will not find this particular discipline listed. Nevertheless, re-enchantment is a natural outworking of other disciplines such as humility and gratitude. Thinking of this process in an orderly way is helpful for us today because of the unusual situation of being at the end of what is perhaps the only disenchanted age that has ever existed. There are many reasons for the uniqueness of disenchantment to our time, not the least of which is scientific advancement, which I would argue is the inevitable consequence of 2,000 years of Christian influence on culture. Many scholars have argued that science itself rests upon profoundly Christian assumptions about the world, without which the discipline is in peril of collapsing in on itself.[4] Science must recover an enchanted way of looking at the world (more on this later).

Perhaps the easiest way to understand how we reached this point comes from Chesterton himself. Our world has sinned and grown old, he wrote; we “are not strong enough to exult in” the endless wonder this world presents us each day.[5]We have lost the ability to rejoice in its goodness — an ability that was easier when Christianity first burst from the grave. We are in an age in which we must discipline ourselves to recover that vitality, though it will look different, for our culture is indeed older. We have seen so much of the genuine sadness of this world that we must learn how to hold both the sadness and hope in our hands at the same time. The same 2,000 years of Christian history have also revealed what damage we can do, even in the name of our Lord. We cannot become blind optimists who refuse to see the genuinely disenchanting elements — the dysteleology that sin has wrought both from within and without Christendom. Additionally, the world is too fallen to deny that there are elements that appear to lack purpose, such as death and disease.[6] On the other hand, we cannot be pessimists who deny that any meaning remains. To be one or the other is to slip back into the tendencies of our pre-Christian ancestors. We must discipline ourselves from falling into either extreme.

Chesterton boldly claims that we must aim to be both extreme optimists and extreme pessimists, and this is truly where genuine re-enchantment begins. He argues that we must approach this world as something that is both strange and secure. He writes, “We need so to view the world as to combine an idea of wonder and an idea of welcome. We need to be happy in this wonderland without once being merely comfortable.”[7] He calls this attitude that of a cosmic patriot. “Whatever the reason, it seemed and still seems to me that our attitude towards life can be better expressed in terms of a kind of military loyalty than in terms of criticism and approval,” he writes, “The point is not that this world is too sad to love or too glad not to love; the point is that when you do love a thing, its gladness is a reason for loving it, and its sadness a reason for loving it more.”[8]

For Chesterton, Christianity is the only system that integrates these opposing needs without watering them down. More importantly, Chesterton notes that Christianity alone takes a view of mankind that combines extreme optimism with extreme pessimism. He writes,

It separated the two ideas and then exaggerated them both. In one way Man was to be haughtier than he had ever been before; in another way he was to be humbler than he had ever been before. In so far as I am Man I am the chief of creatures. In so far as I am a man I am the chief of sinners. . . . We were to hear no more the wail of Ecclesiastes that humanity had no pre-eminence over the brute, or the awful cry of Homer that man was only the saddest of all the beasts of the field. Man was a statue of God walking about the garden. Man had pre-eminence over all the brutes; man was only sad because he was not a beast, but a broken god. . . . The Church was positive on both points. One can hardly think too little of one’s self. One can hardly think too much of one’s soul.[9]

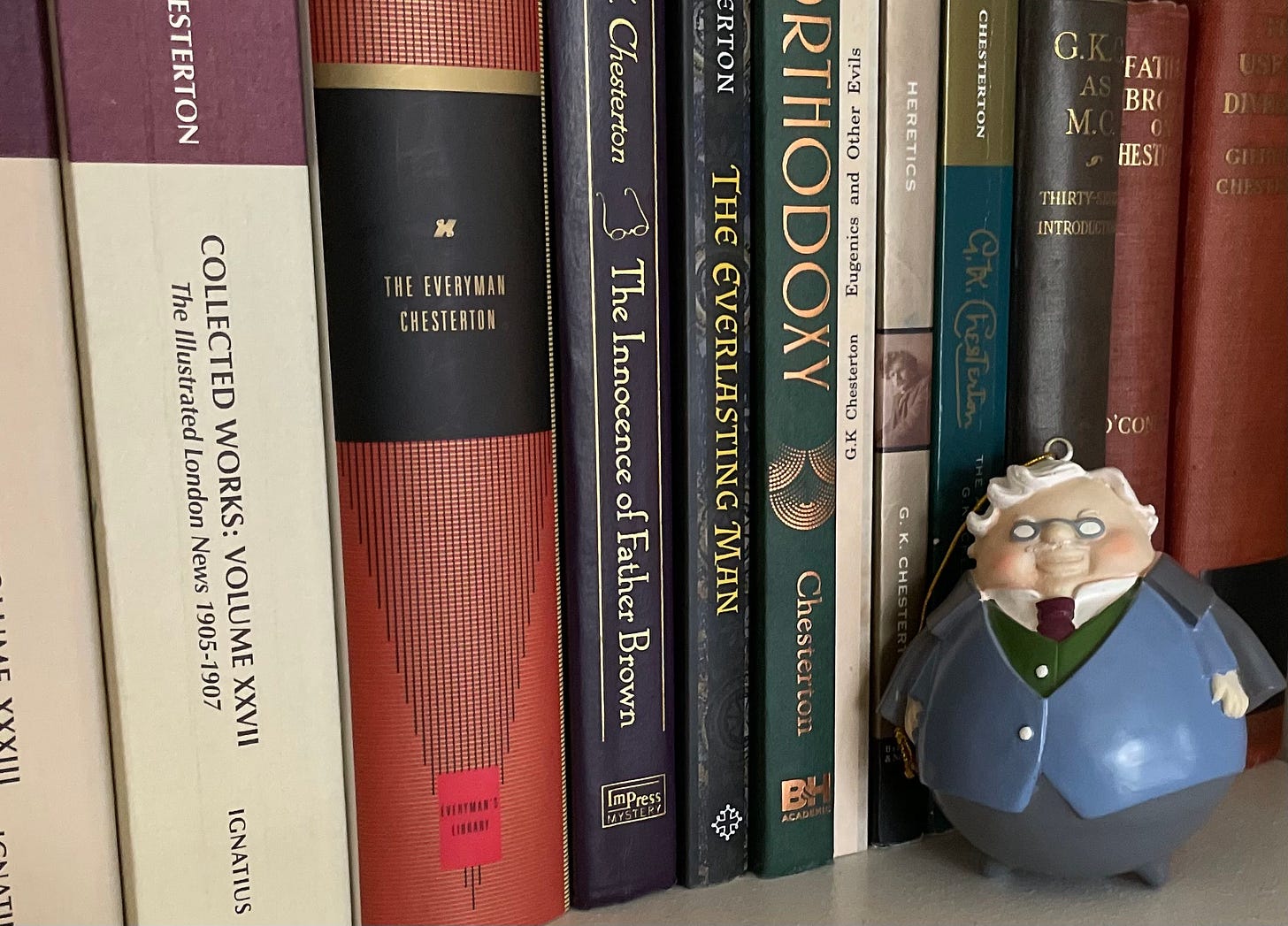

To that end, with this inaugural post, I begin a series for Shadowlands Dispatch that examines how Chesterton embodied this spiritual discipline of re-enchantment. My next installment will cover something near and dear to my heart and vocation: science education. I will argue that the best science education — the kind that fosters genuine knowledge without sacrificing wonder — will begin in Chesterton’s Elfland. In the meantime, let me encourage you to read (or reread!) Orthodoxy.

I cannot recommend the annotated version by Trevin Wax enough. It contains helpful footnotes and introductions/conclusions for each chapter that guide the reader through Chesterton's complex prose and profound insights. Wax also took the liberty to insert a few more paragraph breaks and headings for us modern readers who tend to get lost when a single paragraph persists for more than a page, as it tends to do with G.K.

In addition to Orthodoxy, I recommend reading the essay “Talking About Bicycles” by C.S. Lewis. I believe this piece provides an excellent understanding of the process of enchantment, disenchantment, and re-enchantment. Here is a link to an audio version of the essay.

Enjoy and till next time!

—Rebekah Valerius earned a B.S. in Biochemistry from the University of Texas at Arlington and an MA in Apologetics from Houston Christian University. Her academic interests include the works of G.K. Chesterton, philosophical and literary apologetics, and the philosophy of science. She has written for Christian Research Journal, An Unexpected Journal, and The Worldview Bulletin. She teaches biology and chemistry at a classical Christian school in the Dallas area.

[1] For more on this, see Justin Brierley’s latest book and podcast here: The Surprising Rebirth of Belief in God.

[2] For more on this, read my review of Strange Rites: New Religions for a Godless World by Tara Isabella Burton for Christian Research Journal, “Bespoke Religiosity and the Rise of the Nones”.

[3] G.K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2006), 80.

[4] For more: “Mere Science” by Rebekah Valerius at The Worldview Bulletin Newsletter

[5] G.K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy, 54.

[6] Chesterton makes the following astute observation about pagans who read too much into nature without accounting for its distortions: “Nature worship is natural enough while the society is young, or, in other words, Pantheism is all right as long as it is the worship of Pan. But Nature has another side which experience and sin are not slow in finding out. . . . The only objection to Natural Religion is that somehow it always becomes unnatural. A man loves Nature in the morning for her innocence and amiability, and at nightfall, if he is loving her still, it is for her darkness and her cruelty.” Orthodoxy, 71.

[7] G.K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy, 5.

[8] Ibid., 62.

[9] Ibid., 90.

[1] G.K. Chesterton, The Apostle and the Wild Ducks, ed. Dorothy Collins (London: Elek, 1975)