Reading Chesterton

By Rebekah Valerius

“There is at the back of all our lives an abyss of light, more blinding and unfathomable than any abyss of darkness; and it is the abyss of actuality, of existence, of the fact that things truly are, and that we ourselves are incredibly and sometimes almost incredulously real.”[1]

“I’m beginning to strongly suspect that nobody actually understands G.K. Chesterton,” an acquaintance once remarked. “They just like quoting him when convenient.” I had to laugh at this, for I am guilty as charged. Chesterton both confounds and captivates me, and I am confident that I have quoted him on numerous occasions without really understanding him. He had a way with words that makes the temptation to repeat him too hard to resist — even when his incredible intellect far outruns me. Despite this, reading Chesterton has been one of the delights of my life. He is famous for remarking that Christianity has not been “tried and found wanting,” but rather “it has been found difficult and left untried.”[2] My aim here is to convince you not to leave reading Chesterton untried, as well.

Chesterton is probably best known today for being an important influence on C.S. Lewis. In his autobiography, Lewis wrote that even as a young atheist, Chesterton’s writing made an immediate conquest of him. “I did not need to accept what Chesterton said in order to enjoy it,” he remarked. [3] “His humour was of the kind which I like best . . . humour which is not in any way separable from the argument.”[4] Lewis concluded that he “liked him for his goodness.”[5]

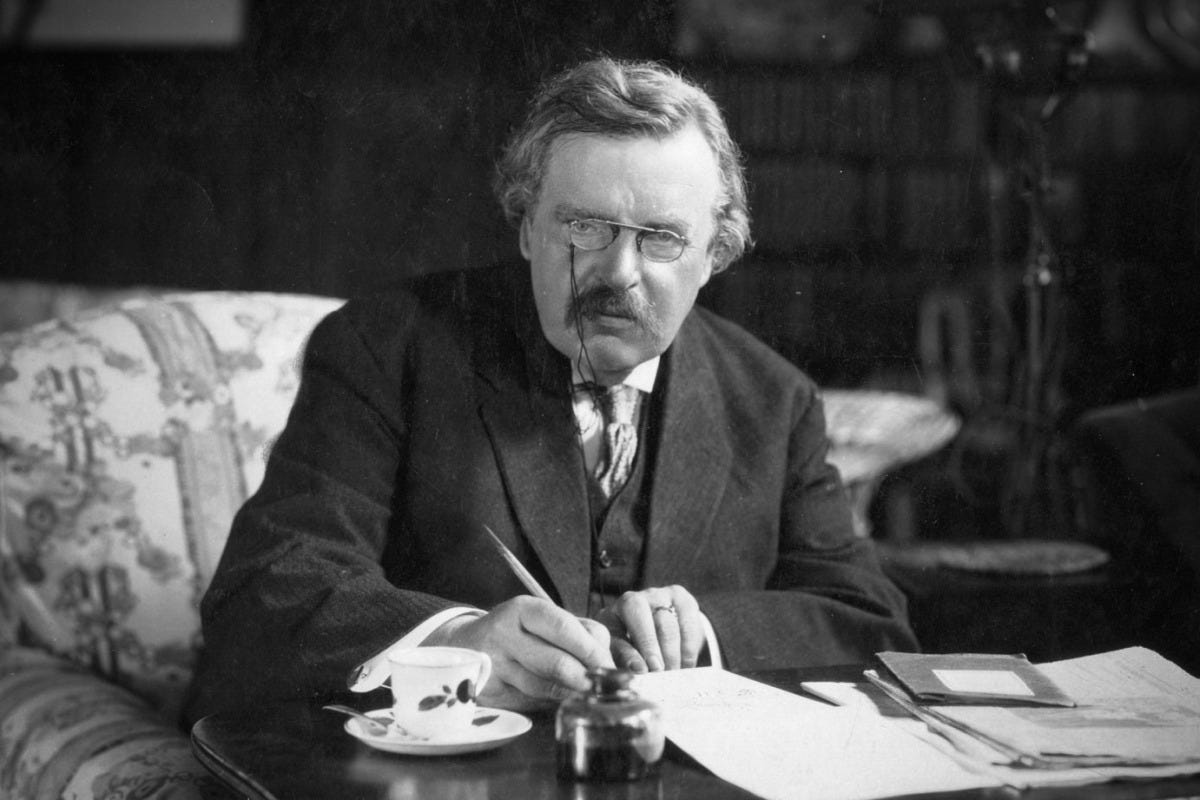

Chesterton was a prolific man of letters whose pen played with the written word in many forms. Novels, short stories, essays, detective fiction, plays, poems, biographies, literary and art criticism, and copious newspaper columns all constitute his massive literary corpus. Given this output, it is not surprising that Chesterton was a household name during his lifetime. Upon his death in 1937, Dorothy Sayers wrote to his wife, Frances, saying, “G.K.’s books have become more a part of my mental make-up than those of any writer you could name.”[6] She was certainly not alone in this perspective. In reading the likes of Lewis, Tolkien, and others, one hears echoes of Chesterton’s influence.

Chesterton’s Influence

One of my favorite insights from G.K. Chesterton is the idea that when a society abandons belief in a supernatural moral order (or religion), not only does it become vulnerable to vices, but it also fails to understand the virtues. Calling them “wild and wasted virtues,” he wrote,

The modern world is full of the old Christian virtues gone mad. The virtues have gone mad because they have been isolated from each other and are wandering alone. Thus some scientists care for truth; and their truth is pitiless. Thus some humanitarians only care for pity; and their pity (I am sorry to say) is often untruthful.[7]

Lewis echoes this observation in The Abolition of Man when he discusses the consequences of society’s attempts to erect ideologies without acknowledging the objective moral order from which they originate. He writes that such a system will inevitably “consist of fragments . . . arbitrarily wrenched from their context in the whole and then swollen to madness in their isolation.”[8] Both thinkers understood that virtues must be properly ordered by an external standard that is entirely independent of us.

Chesterton concluded that these roving virtues are only properly ordered in the towering person of Christ (the Standard Himself!). He likened our Lord, as depicted in the Gospels, to a giant in the land. He wrote, “There is a huge and heroic sanity of which moderns can only collect the fragments. They have torn the soul of Christ into silly strips, labelled egoism and altruism, and they are equally puzzled by His insane magnificence and His insane meekness.”[9]

Chesterton the Re-Enchanter

Insights like the one above illustrate my final point on why you should give reading Chesterton a try. He had a way of expressing seemingly tired truths in ways that breathe life back into them — or rather, that removes the thick film of sin and boredom from our eyes so we can see these glorious truths once more. This is re-enchantment.

Chesterton continually injected a sense of wonder back into the facts that have been dulled by familiarity.[10] Drawing inspiration from Robinson Crusoe, he likened the world to a stranded island strewn with objects that are precious remnants of better days:

It is a good exercise, in empty or ugly hours of the day, to look at anything, the coal-scuttle or the book-case, and think how happy one could be to have brought it out of the sinking ship on to the solitary island. But it is a better exercise still to remember how all things have had this hair-breadth escape: everything has been saved from a wreck.[11]

Chesterton reminds us of the joy of existence — that existence itself is good, something so easily forgotten in the sorrows of this life. “Man is more himself,” he wrote, “when joy is the fundamental thing in him, and grief the superficial. Melancholy should be an innocent interlude, a tender and fugitive frame of mind; praise should be the permanent pulsation of the soul.”[12] Such praise reverberates throughout all of Chesterton’s writing. It is difficult not to be infected by it in turn.

Chesterton's essays are a wonderful place to start. Published in 1909, Tremendous Trifles is a collection of some of his best ones. It's available for free here.

Final advice when reading Chesterton: be patient and allow him to take you on a journey. He may wear you out with his exuberate intellect, but you will not regret it.

You may even find yourself quoting him when convenient.

—Rebekah Valerius earned a B.S. in Biochemistry from the University of Texas at Arlington and an MA in Apologetics from Houston Christian University. Her academic interests include the works of G.K. Chesterton, philosophical and literary apologetics, and the philosophy of science. She has written for Christian Research Journal, An Unexpected Journal, and The Worldview Bulletin. She teaches biology and chemistry at a classical Christian school in the Dallas area.

[1] G.K. Chesterton, Chaucer, http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks13/1300211h.html.

[2] G.K. Chesterton, The Collected Works of G.K. Chesterton Vol. IV (San Fransisco: Ignatius Press, 1987), 61.

[3] C.S. Lewis, Surprised by Joy (New York: Harcourt Brace & Co., 1984), 191.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Crystal Downing, “Sayers ‘Begins Here’ with a Vision for Social and Intellectual Change: Christian History Magazine,” Christian History Institute, accessed July 14, 2022: https://christianhistoryinstitute.org/magazine/article/sayers-begins-here.

[7] G.K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2006), 25-26.

[8] C.S. Lewis, The Abolition of Man (New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., 1955), 56.

[9] G.K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy, 39.

[10] “It is almost impossible to make the facts vivid,” Chesterton wrote with respect to the Gospel, “because the facts are familiar; and for fallen men it is often true that familiarity is fatigue.” G.K. Chesterton, The Everlasting Man (Tacoma, WA: Angelico Press, 2013), 10.

[11] Chesterton, Orthodoxy, 59.

[12] Ibid., 155.